One of the many long term tragedies of wars is the severe cultural loss. Whether by "cultural revolutions" or by the total destruction of a country amid civil war, this loss -- books, art, music, cultural representations and evocations in general -- bears down severe ramifications on its people, including a loss of identity and community and at times a complete misunderstanding or erasure of history itself. I recently read a post on Mitali Perkins' blog, Mitali's Fire Escape, about her brief knowledge/awareness of contemporary Syrian children's literature (or rather, the struggle to find it). Originally, my intent was to search for children's literature in English with Muslim protagonists (featuring either Muslim American children or set abroad). Instead, I read this post and started to pour over the idea of what cultural loss does to children. I recommend reading through Mitali's post to learn about some literature already in existence and the efforts that emerge within refugee camps to give children a sense of identity once more. Children's books in this sense act purposefully to give children an opportunity to reclaim some notion of community (a valuable gift to refugees).

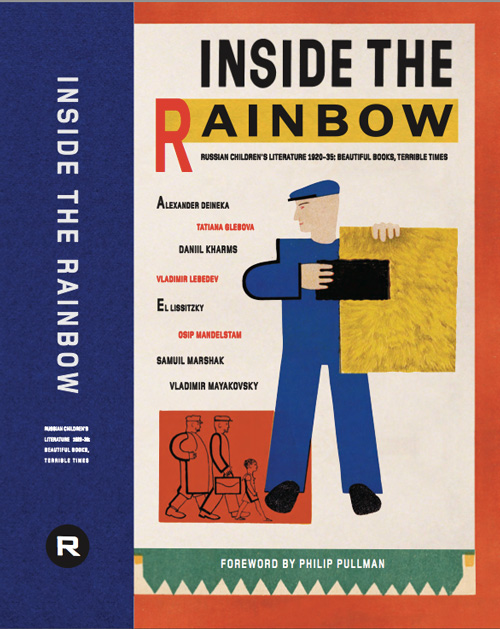

Philip Pullman recently discussed Stalin's purges and the resilient existence and purpose of children's literature during the Great Terror. Specifically, Pullman reviewed Inside the Rainbow: Russian Children's Literature 1920-1935, compiled and designed by Olga Budashevskaya and Julian Rothenstein. This book shares the striking and powerful images and stories of Russian artists and poets who turns to this genre (the child's picture book) to proliferate their political messages. Pullman does a wonderful job of explaining the power and innovation behind the texts and illustrations, but I am most fascinated by the way adults used children's lit in a totalitarian regime; essentially, children's lit became a safe place for subversive thought (and for the adult thinking these thoughts -- far fewer children's lit poets were arrested and killed during Stalin's rule than other authors). We always talk about the safe spaces and dangerous places that exist within children's stories and what these mean for the child (character and reader). This examination can even extend to the spaces that emerge for "safe reading": cozy corners, treehouses, etc. But here we have the children's book serving as the ideal hiding place for adults. It's not a new concept, I know, but the extent to which this lasted is amazing, and is another reminder of how important and necessary children's lit can be, both for kids and grown ups.

This leads to my last link of the day, a brief essay on the transformative power of children's literature, particularly in committed and political books. In it, the author discusses the many ideological perspectives that the books are soaked in, such as: dismantling myths that adults create to "protect" children (e.g., from the realities of society and the existence of homelessness), instilling a drive and understanding for the need of revolution, or bringing awareness to economic issues, unions, and strikes. "Children's literature is a battleground between conserving the status quo and transforming it; between continuity and change."The child as disenfranchised and disempowered citizen becomes the ultimate tool this time, the overarching purpose behind the text, and the key figure who can act on the messages passed on by the authors and illustrators.

Philip Pullman recently discussed Stalin's purges and the resilient existence and purpose of children's literature during the Great Terror. Specifically, Pullman reviewed Inside the Rainbow: Russian Children's Literature 1920-1935, compiled and designed by Olga Budashevskaya and Julian Rothenstein. This book shares the striking and powerful images and stories of Russian artists and poets who turns to this genre (the child's picture book) to proliferate their political messages. Pullman does a wonderful job of explaining the power and innovation behind the texts and illustrations, but I am most fascinated by the way adults used children's lit in a totalitarian regime; essentially, children's lit became a safe place for subversive thought (and for the adult thinking these thoughts -- far fewer children's lit poets were arrested and killed during Stalin's rule than other authors). We always talk about the safe spaces and dangerous places that exist within children's stories and what these mean for the child (character and reader). This examination can even extend to the spaces that emerge for "safe reading": cozy corners, treehouses, etc. But here we have the children's book serving as the ideal hiding place for adults. It's not a new concept, I know, but the extent to which this lasted is amazing, and is another reminder of how important and necessary children's lit can be, both for kids and grown ups.

This leads to my last link of the day, a brief essay on the transformative power of children's literature, particularly in committed and political books. In it, the author discusses the many ideological perspectives that the books are soaked in, such as: dismantling myths that adults create to "protect" children (e.g., from the realities of society and the existence of homelessness), instilling a drive and understanding for the need of revolution, or bringing awareness to economic issues, unions, and strikes. "Children's literature is a battleground between conserving the status quo and transforming it; between continuity and change."The child as disenfranchised and disempowered citizen becomes the ultimate tool this time, the overarching purpose behind the text, and the key figure who can act on the messages passed on by the authors and illustrators.

No comments:

Post a Comment