South Africa and the world lost one of the greatest figures

of peace and justice with the death of Nelson Mandela, who passed away on Thursday. In our time, I can think of no person more devoted to the cause of resistance, anti-apartheid, truth, equality, and forgiveness than him. One could dedicate years to the study of his

words, actions, and their implications; at the very least, we should make ourselves

aware of everything we admired about him and what he stood for, and

continue to uphold those positions in the world around us, no matter how challenging.

“No one is born hating another person because of the color of his skin, or his background, or his religion. People must learn to hate, and if they can learn to hate, they can be taught to love, for love comes more naturally to the human heart than its opposite.”

And few politicians

have had such a rich impact on children as Mandela as well. He found

the child citizens of South Africa his most dear, stating, “There can be no keener

revelation of a society’s soul than the way in which it treats its children.” The depth of

his connection to the youth is captured in The Children’s Mandela, a heartfelt book I came across that includes

letters, responses, and pictures from children across the nation about and to

their Mandiba. The authentic reaction of child citizen to adult leader is

particularly meaningful when we consider the ways in which we waver between

uplifting and suppressing the citizenry of our children, particularly in how we

give them agency and a voice (ours versus their own).

Regarding Nelson Mandela and his radicalized position, I realized upon reflection

that aside from some personal study and a film here and there, my knowledge on

South Africa is woefully dim, all the more when I consider the place, role, and

transformation of children’s literature and childhood. The world may be getting

smaller with the widening scope of globalization and the internet, but pockets

of history face the risk of evaporating in time, leaving new generations

unaware of what truths transpired. So, I did a cursory search to see what books are out there for

children and scholars alike. I found a

few noteworthy children’s books and research starting points in our own SDSU juvenile collection.

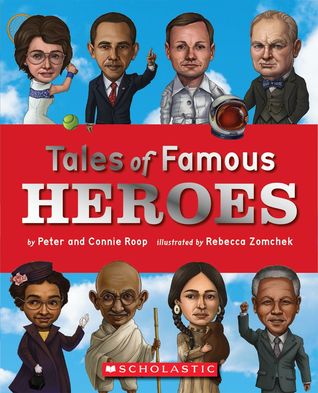

In our library's growing collection I discovered Tales of Famous Heroes by Peter and Connie Roop, which includes the details of the lives and accomplishments of admirable people, including Mandela, with vibrant art and photos and a lot of fun facts.

In our library's growing collection I discovered Tales of Famous Heroes by Peter and Connie Roop, which includes the details of the lives and accomplishments of admirable people, including Mandela, with vibrant art and photos and a lot of fun facts.

I also found The Power of One, by Bryce Courtenay, though the description of this one concerned me slightly. A white South African boy searching for courage, friendship, and an identity during World War II turns to two older men, one black and one white, to show him how to find all that he seeks. It's a coming of age story that grapples with race, politics, religion and wealth, but it specifically harnesses the idea of violence when necessary. Thinking about Mandela's legacy, he too supported guerrilla warfare for a time (until his public renouncement upon release from prison), so the concept is not foreign to South African dynamics, nor to the world.

On a scholarly side, Apartheid and Racism in South African children's literature 1985-1995 offers a useful, if limited, entry point into understanding children's lit around the pivotal decade that saw major changes in South Africa. Also, Jochen Petzold wrote an article for Children's Literature Quarterly titled "Children's Literature after Apartheid: Examining 'Hidden Histories' of South Africa's Past" (Summer 2005). These two texts provide enough historical context and explanation to get even the novice up to speed to the ramifications of apartheid on children's literature, and the ways it has begun to transform.

No comments:

Post a Comment