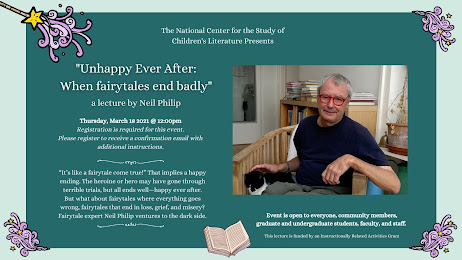

On Thursday, March 18th, the NCSCL was delighted to virtually host Neil Philip for his talk, “Unhappy Ever After: When fairytales end badly.” Well over a hundred listeners joined us through Zoom from both sides of the pond.

The topic that drew so many people to join us was tragic endings. Although most people have come to associate fairytales with the lighter iterations found in Disney adaptations, many of these tales originally end in grief and disappointment. For example, Philip describes how the “greatest of wish fulfillment tale type, Cinderella,” has evolved into a version that ends sadly: in a Brazilian version, Maria’s sister-turned-snake Labismina helps her to escape marriage to her own father but is forgotten when Maria marries a prince. Philip claims that “it is the lonely fate of Labismina that sticks in the mind, not the happy one of Princess Maria,” and goes on to reference Zuni and Eastern Indian versions of this tale with their own tragic endings. He acknowledges that there are also tales that purposefully twist listeners’ expectations of a happy ending via comedy, such as the “English gypsy variant of The Water of Life” told by Taimi Boswell.

He then transitions into a text that is much more familiar to the audience -- that of Little Red Riding Hood. Perrault’s 1697 version is the one with the question-and-answer dialogue that we recall, but in the Brothers Grimm iteration, Red Riding Hood is eaten along with her grandmother and a woodsman cuts them free from the wolf’s belly. Even more gruesome, however, are the French versions, one of which can be found in Catherine Orenstein’s Little Red Riding Hood Uncloaked. In this tale, the wolf serves the girl her own grandmother’s flesh, but the young girl manages to escape by claiming she needed to relieve herself. Philip adds a factual tidbit here about the standard three-volume book wherein one can find over 2,000 folktale types across cultures -- Little Red Riding Hood is listed at ATU-333.

Philip notes that even the Grimm brothers’ darker fairytales are a result of altering the original tales to be lighter. Grimm adds what Philip calls a “literary flourish” to the juniper tree tale, which concludes with a happy ending after “a story that is relentlessly miserable.” Dark themes and other key elements carry on through the iterations of stories. Hans Christian Andersen, the author of the original tales of many fairytales we know today, often writes with themes of grief, suffering, and disillusion. Philip explains that Andersen was rarely one to write happy endings, instead the iterations are “infused with melancholy” and he was “merciless to the characters'' in his tales. Although these happier stories are more popular, Philip quotes Oscar Wilde, “there are times when sorrow seems to me to be the only truth.” Ultimately, Philip says, storytelling can be seen as an act of reparation for the world.

Partway through the talk, an ill-intentioned attendee unmuted himself and interrupted with inappropriate comments. Thankfully, Natalie moved quickly to kick him out and reported him immediately. The lecture resumed without incident, though we were no longer able to admit latecomers.

After Philip concluded his lecture, the chat was opened up for questions which came pouring in. A few of them, along with Philip’s responses, are listed here:

Q: Why do you think children are associated with fairy tales?

A: It started with the Grimm's; they called their collection “Children’s and Household Tales.” The children’s section was really quite short, but as they released newer editions, they realized children were being read these stories, so they softened quite a lot of the elements. Evil mothers become evil stepmothers, for instance. By the end of the 19th century, you get really influential series of books of fairy tales which are specifically aimed at children. The stories are made more acceptable for a child audience. So that’s the beginning of our assumption that fairy tales are expected to be enjoyed by children.

Q: What do you think is the appeal, aesthetic or psychological, of tragic fairy tales?

A: It’s the same as the appeal of horror films and gothic novels; it’s just part of human nature that people like sad things as well as happy things. It is fair to say that the majority of traditional fairy tales do end up with a happy ending, but they put the poor protagonists, both male and female, through the most terrible suffering and troubles along the way. So the happy ending, what Tolkien called the eucatastrophe, is won through suffering.

Q: Why do you think people have edited the original fairy tales to something that can now be read to children?

A: The Victorians -- well, 19th century people; let’s not say Victorians since the Grimms’ first version came out in 1812 -- they were sort of prudish about what was suitable for children. It’s interesting what they thought was suitable, like terrible retributions at the end of fairy tales like Cinderella's sisters getting their eyes being pecked out by doves and people being made to dance in red hot shoes regarded as perfectly acceptable. But they tried to weed out the sexual elements. It’s just part of the transition of these stories from an inherited oral folkloric inheritance to a literary one. People like Angela Carter have tried to put back all the things that were taken out.

Q: It’s refreshing to hear a scholar identify ways their thinking has changed as you mention with the Fens tale or your conception of authenticity’s value or otherwise. Have you experienced any other major shifts in your thinking over the years, scholarly or otherwise?

A: That’s certainly an example when my mind has been changed by someone else’s scholarship. I’m very much more aware of the individual voice of the storyteller in the story and that’s what I value in any particular story, rather than having a more generic interest in Snow White stories, let’s say. That and an interest in all the other elements in a story: the language, cadence, intonation, pauses, gesticulations. The relation between the storyteller and the audience is a very potent, dynamic thing in storytelling. My thinking about folk and fairy tales has remained much the same, but deepened and widened. There are things such as Mrs. Balfour stories where I’ve had a change of heart and thought. I’ve just written, for the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, a biography of a woman called Ruth Tongue, who was a very famous storyteller in the second half of the twentieth century in England. My initial attitude was that Ruth Tongue was basically a fraud, which I thought since I heard recordings of her actual voice: very cut-glass, upper class English and her storytelling voice which is a very heavily accented Somerset dialect. I thought that something is not right here. And learning more about Tongue, I’ve begun to think she is not correct in what she says about where she learned these stories and who she learned them from because it doesn’t stack up, but actually it makes her more interesting as a creative storyteller because she is basically making all this stuff up. Someone said she “collects from herself,” which I thought was a very polite way of putting it.

There were many other questions and answers which we were not able to fit in this blog, but it seemed that many people were able to enjoy the fruit of Philip’s scholarship! His clear expertise, thorough research, and insightful conclusions sparked ongoing conversation on this compelling topic. Even Philip’s cat had something to add! Thank you to those who attended our first virtual scholarly talk. We were delighted to have such an engaged audience.

For those who missed it, the lecture and Q&A were recorded and can be found here:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dBzElceP2nE

Our next guest lecture will be in April; keep an eye out for the details! In the meantime, we hope you pick up a tale that ends unhappily ever after.

No comments:

Post a Comment